Runway Strip Excursion: Bad Luck or Unintended Consequence?

A little over a week ago, there was another spectacular runway excursion event caught on film and shared across social and traditional media. On the 7th April, 2021, a DHL 757-200 veered off the runway at Juan Santamaria airport in Costa Rica. The aircraft was returning to the airport after declaring an emergency due to a hydraulic issue. The aircraft appeared to have landed safely but towards the end of its roll-out, it veered to the right and came to rest in a low area with its nose high and tail broken. Luckily, this was a freighter flight and the crew evacuated safely.

Runway excursions are, according to EUROCONTROL, IATA and others, the most frequent accident type in aviation. Despite efforts to and wins in reducing runway excursion rates, the raw number of excursions and their potential for significant fatalities keeps them in the top risk category.

As I checked in on this event, I noticed the potential for us to revisit an old question about runway strip widths and the acceptability of an aircraft departing the runway strip - see Is this Acceptable? When a runway strip isn't wide enough.

Dan’s (Consistently) Poor Artistic Skills

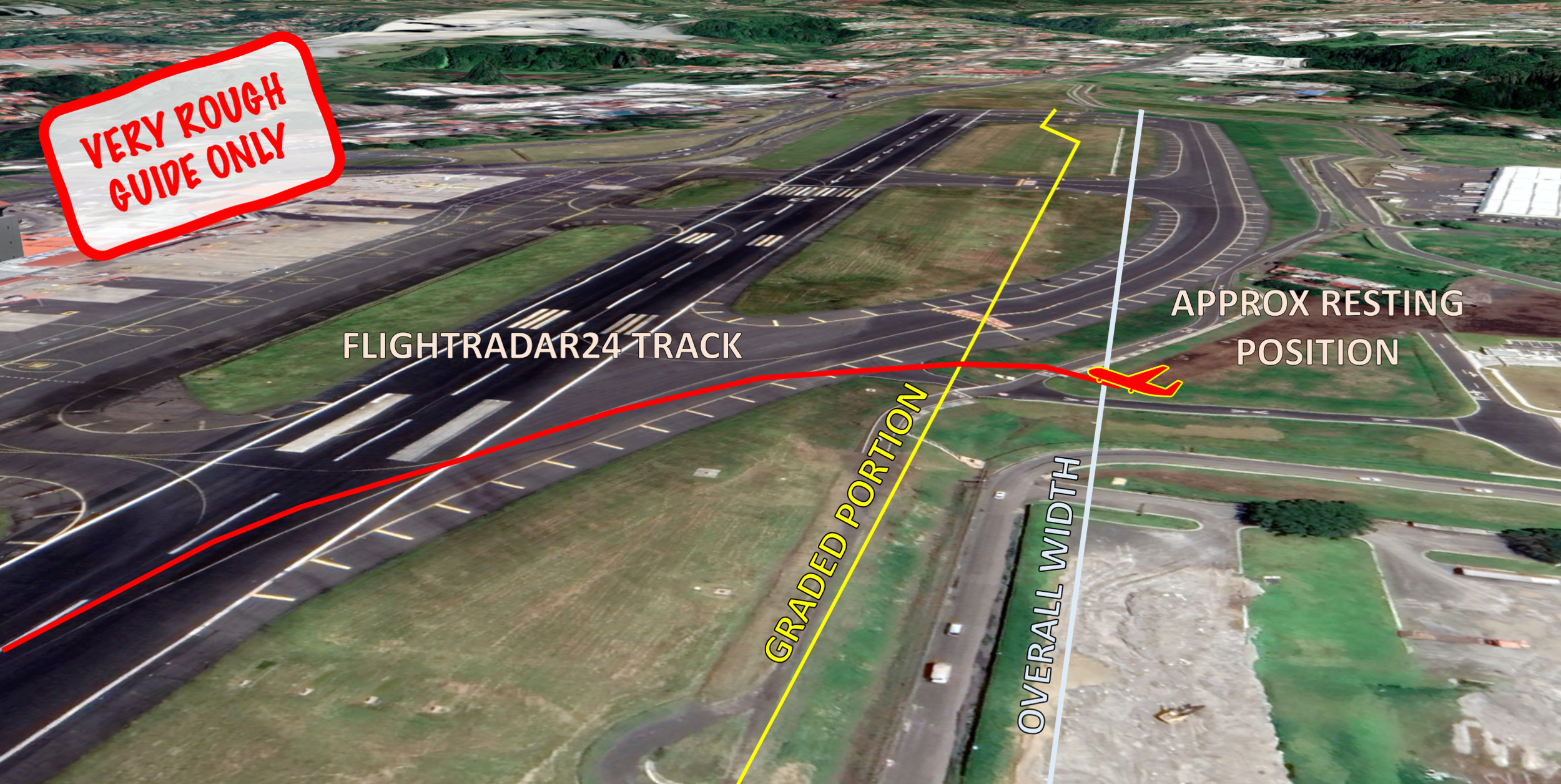

I think most airport safety nerds would have been instantly curious in the runway strip standards at this airport after viewing the footage and/or seeing post-crash photos with the last moments of the accident seeing the aircraft descend into some sort of ditch. So, I set about drawing another picture using Google Earth and the standards contained in Annex 14 as a guide.

As a ground-based veer-off event, this aircraft, like the Pegasus aircraft at Trabzon, ended up outside the portion of the runway strip designed to protect it. This makes the ditch roadway and other structures with which the aircraft collided not so much of a standards issue.

Instead, I started to speculate as to why did this aircraft not remain within the expected boundaries of the runway strip.

Unintended Consequences?

Modern runways at high-capacity airports are serviced by lots of taxiways. Minimising runway occupancy time is essential to managing peak traffic loads. These taxiways often include a mixture of standard intersection taxiways (generally, at right angles) as well as low-speed and rapid exit taxiways. These taxiway entries and exits can add quite a bit of tarmac to the airport movement area. Runway strips have typically been natural or minimally-prepared surfaces which would tend to be softer than regularly trafficked areas.

Looking at the track of this particular aircraft as it veered off the runway, I can’t help but speculate that its path didn’t provide the expected deceleration a natural surface runway strip would provide.

Have our assumptions regarding the dimensions of runway strips and the deceleration characteristics of runway strip surfaces been undermined by modern runway design practices?

Sealed to Natural Surface Ratio

Should a ratio of something like sealed surface to natural surface be considered when assessing the risk of veer-off runway excursions?

This ratio could be calculated using the runway strip (graded portion) width and length minus the runway width and length (& shoulders, if applicable) together with the area of all the taxiways and other sealed surface areas within the runway strip.

Now, the following are some very rough figures but a very simple 2,000 m runway with a single taxiway has an S:N surface ratio of around 0.5% which increases about 0.5% for every conventional taxiway added. Each rapid-exit taxiway might increase the ratio by 2%.

I did an very, very, very rough calculation of this ratio for 09R/27L at Heathrow and found that it’s S:N surface ratio of around 30%.

Or Maybe it was just Bad Luck

I honestly don’t think there is the data to support a big shift in this area but it was, for a moment, an interesting concept to think about. Veer-off events, per IATA, are more common but they have not led to the fatalities that landing overruns do.

If the large tarmac area at Juan Santamaria is found to have contributed to the extent of the runway excursion in this latest case, it will mostly like be considered as just a case of bad luck.

Header image: Grabbed off Google