ASW #1: COVID-19 & Safety: A Bow-Tie Risk Assessment Approach

Today’s theme is “maintaining airport safety through COVID-19”. Obviously, this can be a big topic. There are thousands of ways COVID-19 has impacted our daily lives - some large and some subtle. So, in thinking about this topic, I wanted to create a structure we could use to analyse the virus’s impact.

For me there are two distinct categories of impact:

COVID-19 as a hazard to passengers and personnel, and

COVID-19 as an impediment to how we manage or have managed safety.

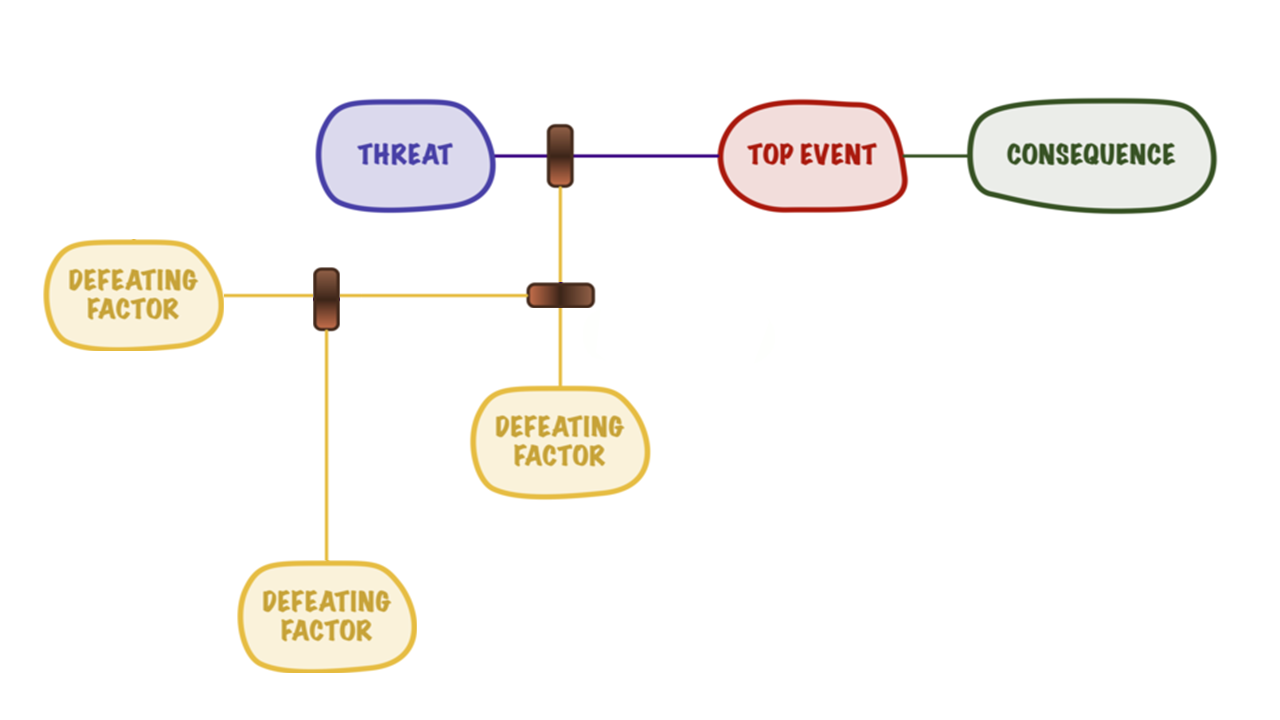

As I started to develop these ideas, an old model I have previously written about came to mind. A long time ago, I wrote a series of articles about the Bow-Tie method of risk assessment/analysis. And in one of these posts, I looked at threats (or hazards) versus defeating factors (or escalating factors) and their relationships to controls. To help discuss these relationships, I came up with the concepts of primary lines and secondary lines within a Bow-Tie risk model.

I think this distinction is very important because:

Many people, including the purveyors of related software platforms, incorrectly list defeating factors or failed controls as their threats,

Different types of controls should be used against threats versus defeating factors (see my previous post), and

COVID-19 is both a threat and a defeating factor.

Viral Dualism

Because COVID-19 is such a pervasive phenomenon, not only does it pose a threat to our bodies, our health and our lives, it affects how we live our lives. The things we do or did to earn a living, learn, have fun or care for each other have been disrupted in fundamental and devastating ways.

And airport safety has been and is being impacted in exactly the same way.

As a threat to passengers and airport personnel, we see daily its impact - masks, gloves, temperature screening, hand sanitiser everywhere, even UV-light robots. In a very broad sense, I think we are getting better at this. There are still plenty of challenges with the evolving science and communicating with or educating segments of our population.

It appears to me, that this side of the concern is covered fairly well in our authorities’ public health advisories and international guidelines. Airport Safety Week’s own material on the subject is heavily focused on COVID-19 as a direct threat.

COVID-19 Diversion

But the more insidious impact of COVID-19 has and will continue to be the way it has made us change how we do things. Things like switching to remote meetings, some personnel working from home, limits on face-to-face training or even extensions on re-training or re-qualification time frames.

Individually, all these decisions make perfect sense when viewed from perspective of COVID-19 as a threat. But what has been the cumulative impact on our pre-existing safety controls?

Take in-person meetings for example - I imagine most people would consider on-line meetings to be a suitable substitute and think that there has been little impact on their effectiveness as a safety control (probably on the secondary line).

However, when I think back to the weekly operations coordination meeting I held in a previous job, I recognise that, in the sidelines to that meeting, either before or after, many conversations on important safety and operational issues would be had. They we often talk about things either too small to discuss with the whole group or still preliminary to a full discussion. But the cumulative impact of these small interactions would have been having a positive impact on safety every week.

And that is not even considering the social interactions that would open and support good relationships in the meeting. Asking what someone has planned for the weekend helps to establish a human connection and rapport. And this, in turn, facilitates communication on other issues.

Do we get as much out of our meetings under the new paradigm?

COVID-19 Erosion

COVID-19 has also induced a significant air traffic downturn and that, in turn, has impacted the availability of resources - both money and people. Reductions in budgets and personnel will then impact on our safety controls in a multitude of ways.

For example, aerodrome serviceability inspections on a large aerodrome might have been, pre-COVID-19, completed by a number of people in coordination. This is good practice as it can minimise movement area unavailability, provide some overlap on visual scanning, and shorten visual scanning time per person.

However, a team of the size required to complete inspections this way might not be justified with traffic levels being what they are now. It is still safe to complete an aerodrome serviceability inspection with one person, providing that the entire movement area is covered they required number of times, but it does introduce new defeating factors that require attention and control.

Fatigue and complacency are two significant human factors that should be recognised as a bare minimum. Training and support can help alleviate the impact of these and other nature human performance issues.

The important thing is that we acknowledge these differences and address, where we can, their impact on our management of safety generally.

Back to the Model

Within the Bow-Tie model, there is no limitation to introducing a tertiary line. I often acknowledge defeating factors to the second or third level - just as a way of thinking about our controls at a deeper level.

While I have received trusted, personal advice to limit my Bow-Tie risk analysis to one level of defeating factors (the secondary line), if ever there was a time to deepen our analysis of risk, it is now. COVID-19 has rocked the foundations of our society - how often have you heard the phrase, “the new normal?”.

Tomorrow’s theme is human factors and I love this subject so much. The hard part is going to pick just one thing to write about.

Images: Header: Karolina Grabowska (via Pexels), Girl in Airport: Anna Shvets (via Pexels) & Diagrams: Dan Parsons